pre diabetes in children

Prediabetes: How to identify children at risk

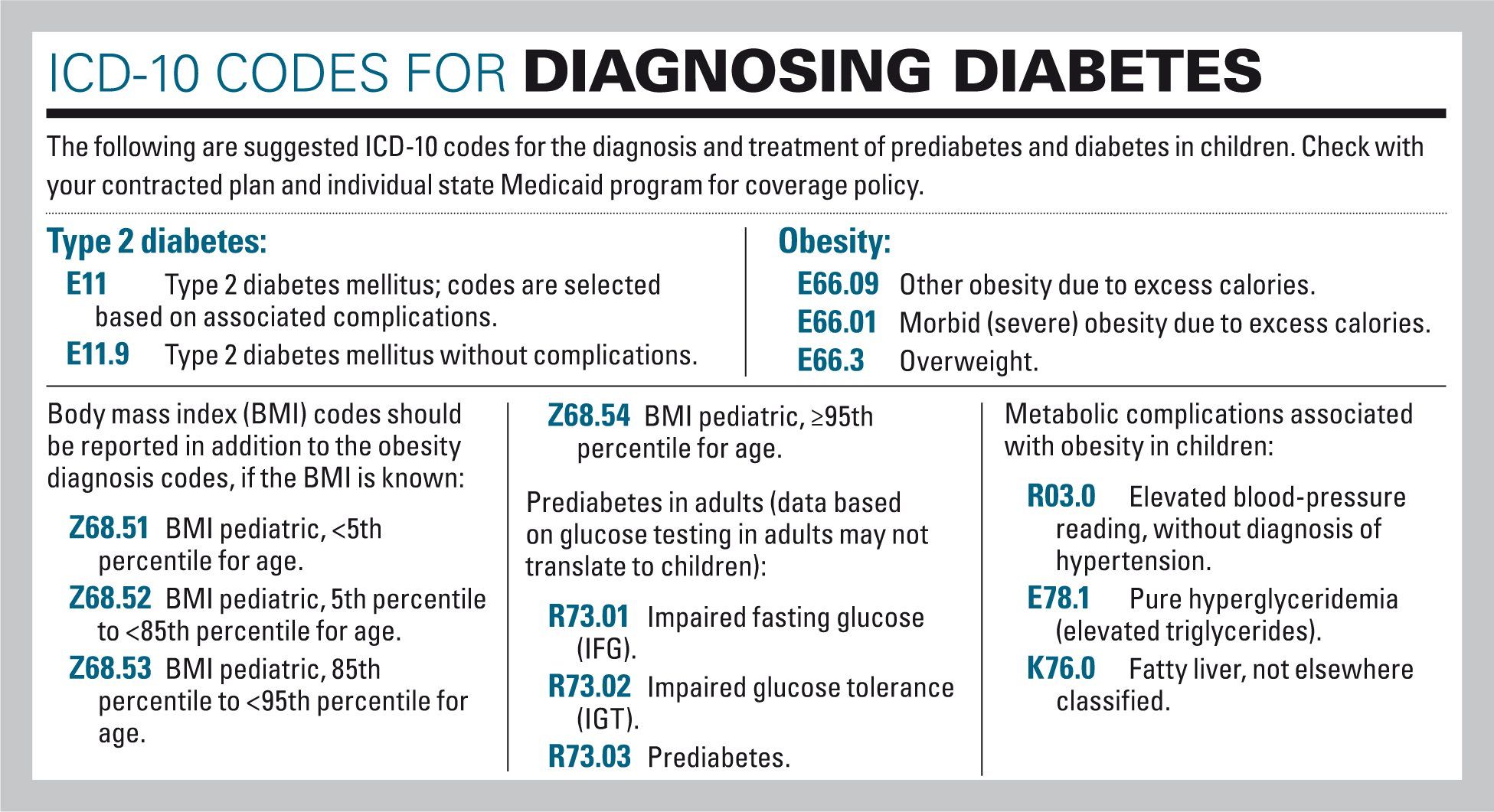

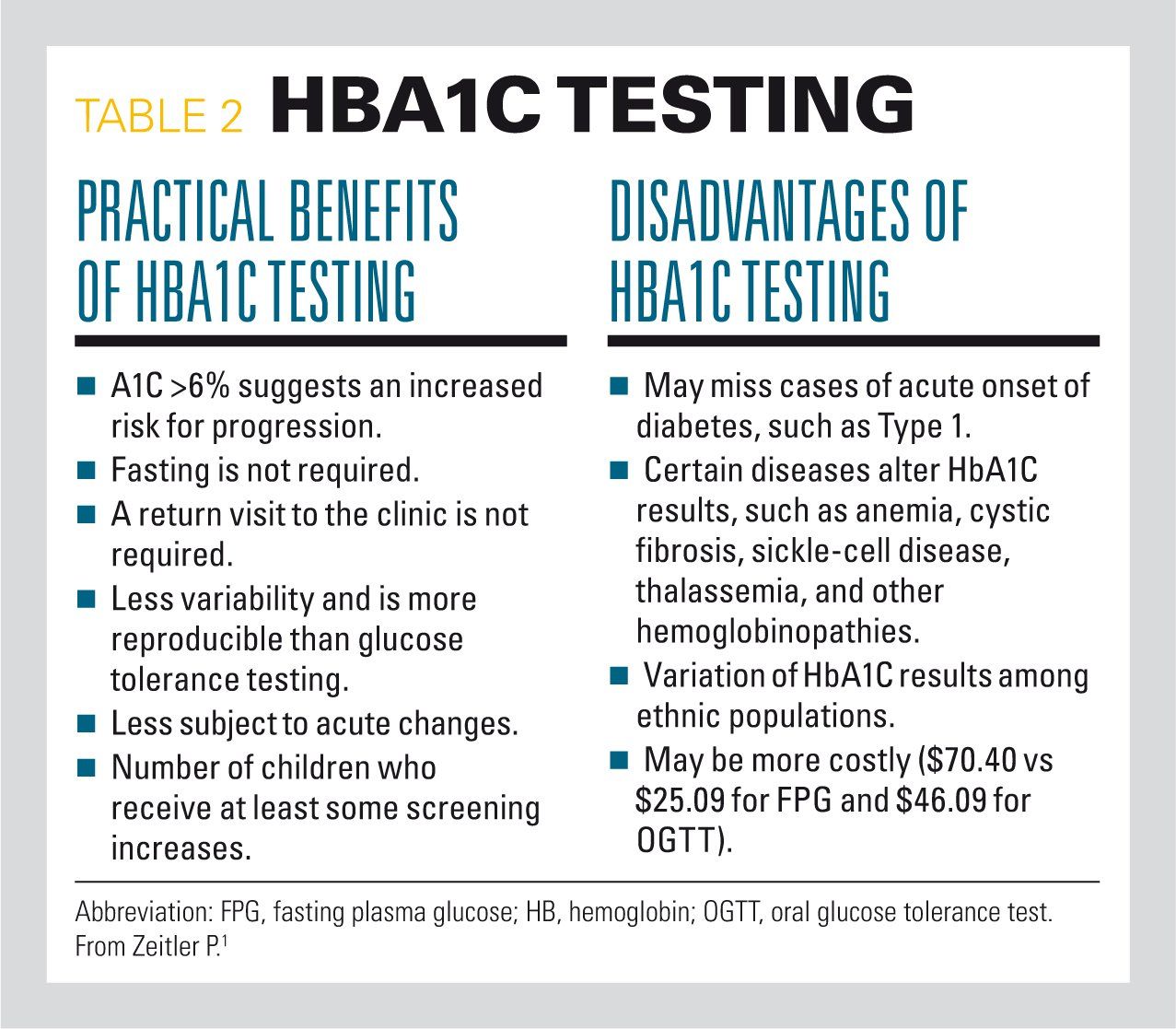

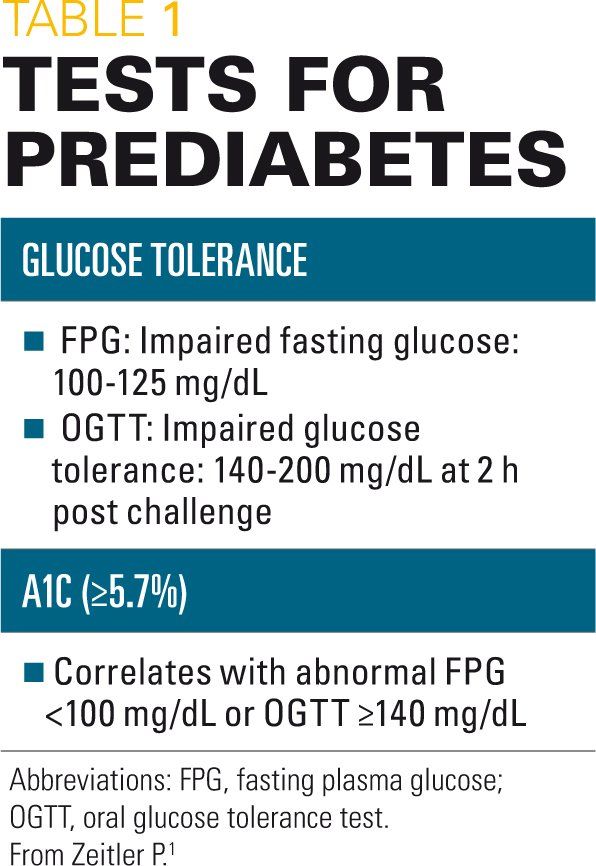

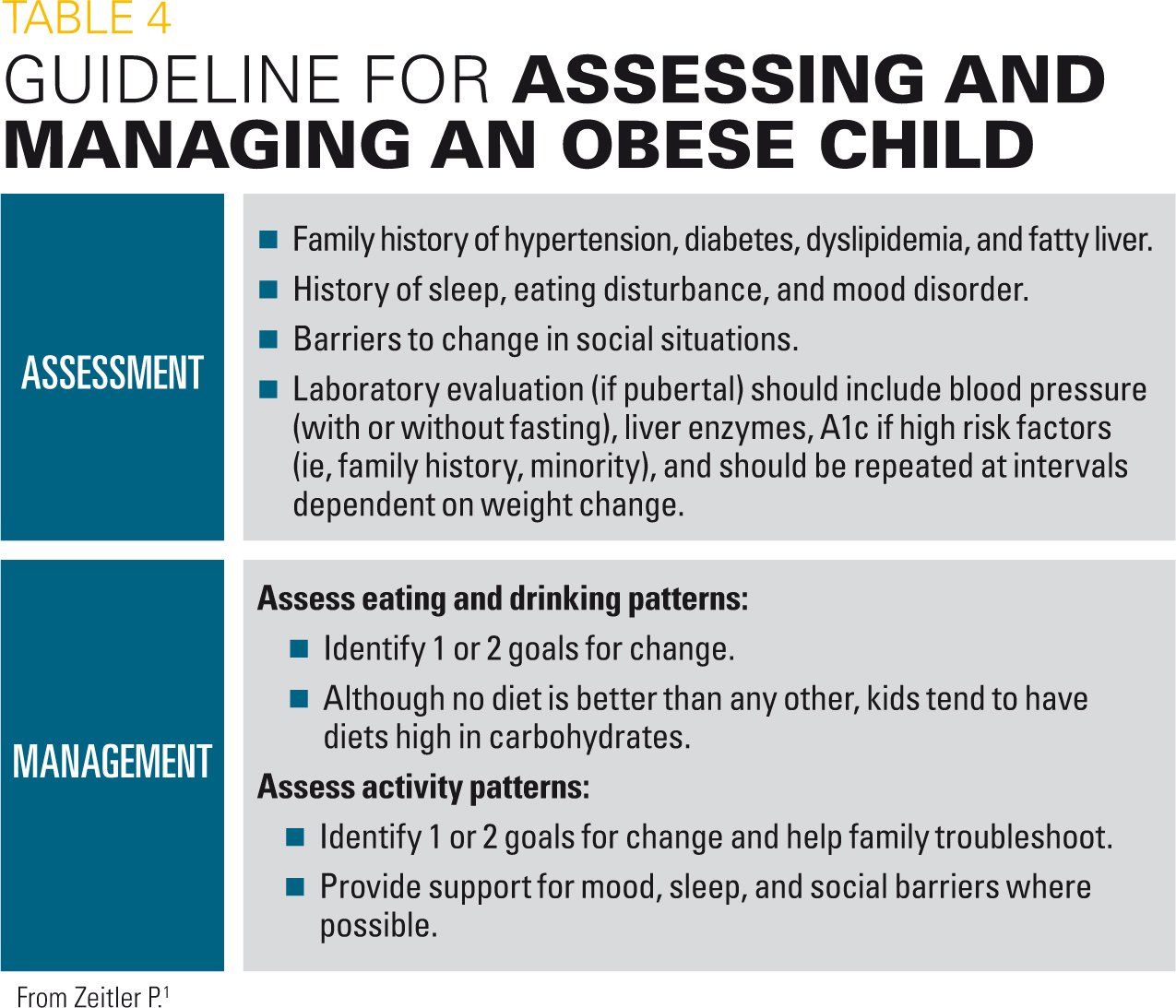

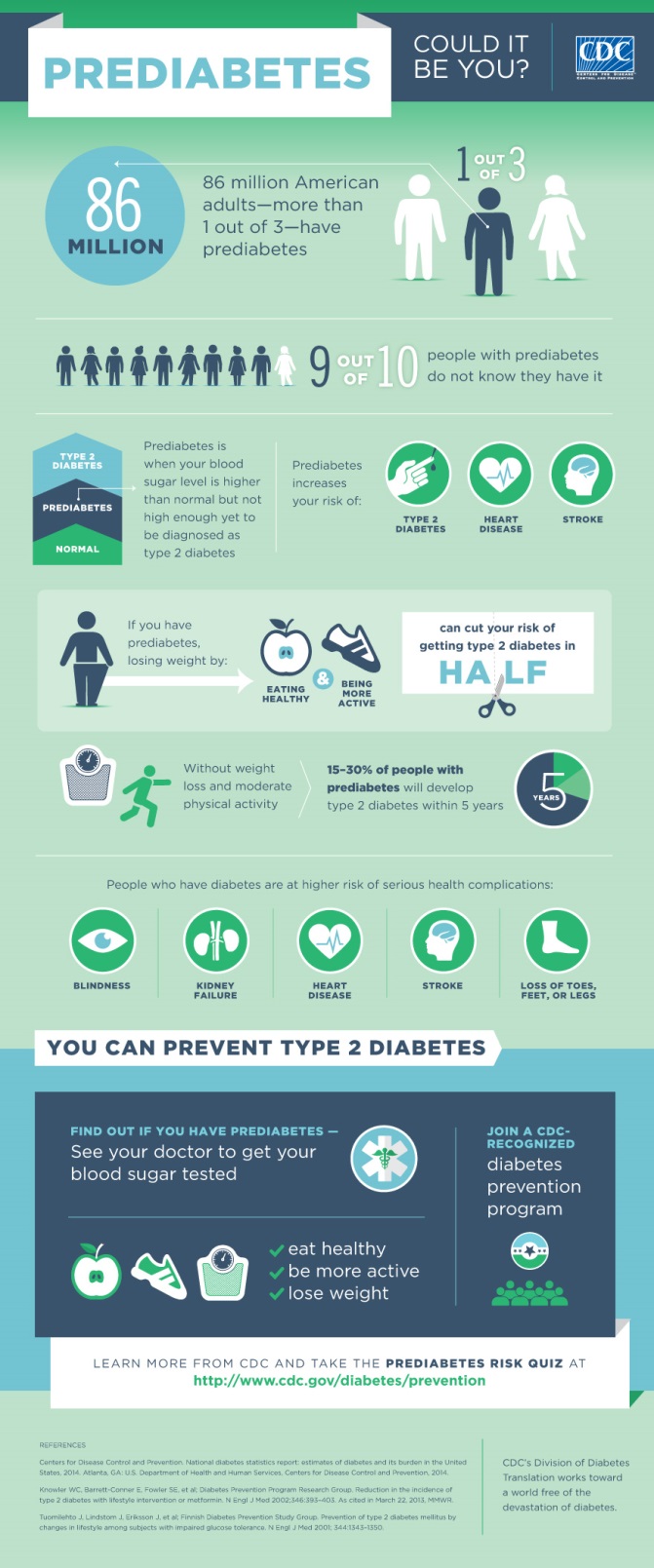

Prediabetes: How to identify children at riskWarning: The NCBI website requires JavaScript to operate. Treatment of Prediabetes in Child Obesity Treatment Programs: Support for Research and Practice Current Matthew A. Haemer1Department of Pediatrics, Nutrition Section, Faculty of Medicine of the University of Colorado, Aurora, CO.H. Mollie Grow2Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine of the University of Washington, Seattle, WA.Cristina Fernandez3Department of Pediatrics Gloria J. Lukasiewicz4Children's Hospital Association, Alexandria, VA. Erinn T. Rhodes5Endocrinology Division, Boston Children's Hospital, Boston, MA. Laura A. Shaffer6Department of psychiatric and behavioral sciences, Faculty of Medicine, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY. Brooke Sweeney7Department of Pediatrics, Faculty of Medicine, University of Louisville, Louisville, KY. Susan J. Woolford8Department of Pediatrics, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, MI.Elizabeth Estrada9Division of Endocrinology, Connecticut Medical Center, Hartford, CT.AbstractBackground: Diabetes mellitus type 2 (T2DM) and prediabetes have increased in prevalence among children with overweight and obesity, with significant time-to-to-to-term implications. There is little evidence published about the best approaches to the care of prediabetes among overweight youth or the current practices used in pediatric weight management programmes. Methods: This article reviews literature and summarizes current practices for the detection, diagnosis and treatment of prediabetes in child obesity treatment centers. The findings on current practice were based on responses to an online survey of 28 pediatric weight management programmes in 25 child hospitals in 2012. On the basis of the literature examined, and empirical data, consensus support statements on the care of prediabetes and the prevention of T2DM were produced among the representatives of these 25 obesity clinics for children ' s hospitals. Results: The revised evidence shows that the current diagnostic parameters of T2DM and prediabetes are derived from adult-based studies with little understanding of clinical outcomes among young people. There are very limited evidence to prevent progression of prediabetes. Some evidence suggests that a significant proportion of young obese with prediabetes will return to normoglycemia without pharmacological management. Evidence supports lifestyle modification for children with prediabetes, but a deeper study of specific lifestyle changes and pharmacological treatments is needed. Conclusion: Evidence to guide the management of prejudices in children is limited. Current practice patterns of pediatric weight management programs show areas of variability in practice, reflecting the limited evidence base. More research is needed to guide clinical care for young people with overweight prediabetes. Introduction Increased prevalence of obesity, especially severe obesity, in all pediatric age groups, has been accompanied by an increase in type 2 diabetes mellitus (T2DM), prediabetes and insulin resistance (IR). Along with other obesity comorbidities, including hypertension, dyslipidemia, fat liver disease, musculoskeletal disorders and cardiovascular disease, T2DM and its complications represent a significant cause of long-term disability within the U.S. population and a challenge to the resources of the U.S. health system. However, there is little evidence in pediatric populations for effective T2DM prevention and treatment. At present, one third of American youth are estimated to be overweight or obesity, and up to 15% of adolescents may have prediabetes and/or diabetes. Adolescents and young adults with T2DM are expected to lose 15 years of their life expectancy and may experience serious and chronic complications for their years of life., Most diagnostic tools and therapeutic interventions currently in use for pediatric T2DM are based on extrapolated information from adult literature. However, physiopathology and treatment response vary between children and adults. The TODAY study, the first long-term study of children with T2DM, and others have reported a faster progression of T2DM and betacellular failure in children, compared to adults, and poor treatment results. Data collected between 2001 and 2005 as part of the SEARCH study, a comprehensive and multicenter study of diabetes diagnosed by doctors among young people aged 0 to 19, provide estimates of prevalence and incidence of T2DM by age and ethnicity. The prevalence of T2DM in 2001 was lower among non-Hispanic white youth aged 10-19 to 0.18 in 1000, with an incidence of 3.7 per 100,000 person years during the 4-year study. The prevalence and incidence rates were higher among African Americans (1.06 in 1000; 19.0 per 100,000 person-years), Hispanics (0.46, 11.6) and young Asians and Pacific Islands (0.52, 12.1) than non-Hispanic white youth, with the highest rates among Navajo youth (1.45; 27). The impulse to complete this study of current practice and the examination of current tests is derived from the high prevalence of childhood and adolescent obesity, the increase in the diagnosis of prediabetes and T2DM, and interest in previous identification and prevention., The main objectives of the article are to identify test-backed practices and to report on the consensus of current practice among child obesity specialists for two areas: (1) the detection of pre-betesity and teensic pre-pre-premathrencies2 This article describes the practices of medical weight management clinics, but it is also relevant to primary care providers that administer obese children in collaboration with weight management programs or those that need to address these problems without access to the weight management of outpatient tertiary care. The article also highlights the subsets of the pediatric population identified as having unique needs or differences with respect to the diagnosis and management of pre-birth patients. MethodsThe clinical practices included in this review and bibliographic survey were identified by consensus of the FOCUS Medical Management Committee on a Future Fitter Group (FFF), sponsored by the Association of Child Hospitals (CHA). More than 5 years (2008-2013), the FFF group of more than 100 representatives of 28 weight management programs in children's hospitals in the United States met in person quarterly and on a weekly basis. Each institution was self-elected to participate in the FFF through a request process available for 250 member institutions of the ACABQ. The FFF group was unique during this period of time as a multidisciplinary longitudinal working group of clinical experts and researchers focused on the treatment of childhood obesity, especially severe obesity. The components of the practice were included in this survey and review because the committee judged each to raise relevant clinical issues, have uncertain support for testing and/or are possible sources of variation in care. Current practices are reported from a survey of 28 pediatric weight management programs in 25 children's hospitals with wide geographical distribution in the United States. The study was completed by at least one supplier from each of the participating sites in the FFF group in 2012. Three hospitals had more than one obesity clinic or program using different clinical approaches and therefore completed a survey for each program to capture the variation of practice. The FFF Interprofessional Medical Management Committee (the Committee) described the quality of the available evidence and determined the strength of support for each practice using a framework described by the Steering Committee of the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) on Quality Improvement and Management. The quality of the tests that support each practice was assigned as: A. well designed randomized and controlled trials (RCTs) or diagnostic studies on relevant populations, B. RCTs with minor limitations or overwhelmingly consistent observational studies, C. Observational studies, or D. Expert opinion. The quality of evidence and balance of benefits and damages for each practice were weighed to reach a consensus statement in the following categories: strong support for practice; support for practice; option to consider practice; non-position; or non-supporting statement for practice. The Committee ' s conclusions were presented at a meeting of the entire FFF group, which incorporated the views. The revised statements were adopted by the entire FFF group as consensus statements. Members of the following disciplines participated in the review process: pediatricians, pediatric endocrinologists, dietitians, psychologists, social workers, exercise physiologists and physical therapists. The group identified opportunities for further research based on evidence reviewed and variations in current practice. Results Risk identification The American Diabetes Association (ADA) Committee of Experts on Diagnosis and Classification of Diabetes Mellitus first recognized prediabetes in 1997. Prediabetes can be defined by abnormal glucose regulation, including impaired fasting glucose and/or impaired glucose tolerance (GTT) and/or glucose hemoglobin glucose (A1c). Data from adult and adolescent studies have shown that prediabetes, especially in those with a high BMI, significantly increases the risk of developing diabetes, but is reversible. In one study, up to 50% of adolescents with severely obese prediabetes returned to normal glucose tolerance for 20 months, while 24% showed progression of prediabetes to diabetes, and those with the highest risk of disease progression. Another study showed that 75% of obese white teens with IGT returned to normal glucose metabolism, while 2% progressed to diabetes. Based largely on data from the study of the Diabetes Prevention Program Research Group (DPP) which shows successful delay or prevention of the initiation of T2DM in adults, there is growing interest in early detection of prediabetes in childhood. Clinical tests Medical providers who routinely perform obese child lab tests, as recommended by professional societies, will likely identify some children with blood glucose or A1c measurements in the range of prediabetes. summarizes recommendations for the detection of T2DM adapted to the 2007 Committee of Experts ' recommendations on the prevention, evaluation and treatment of overweight and obesity of children and adolescents. Table 1.Type 2 Diabetes Screening in Asymptomatic Pediatric Patientsa,BMI criteria for screening 1. All children or adolescents who are severely obese (BMI √99th percentile) 2. Children or adolescents at the early age of 10 or early puberty with a) Obesity (BMI ≥95to percentil) b) • T2DM family history in first or second grade • High-risk/ethnic career (African American, Latino, Native American, Asian American, or Pacific Islander) • Insulin resistance signals or conditions associated with diperlica resistance Less than 10 years, or prepuberal if the child has the BMI percentile or has one or more additional risk factors. Retesting • Biannually if it is normal, more often for abnormal values, fast weight gains, development of other comorbidities (hypertension or dyslipidemia), and/or appearance of puberty. SGAPs, second-generation antipsychotics. Special risk populations In addition to obesity, multiple factors add to the risk of diabetes and justify consideration., Genetic and environmental risk factors include female gender, sedentary behavior and T2DM family history. Teens are 1.7 times more likely than children to develop T2DM., At least 74% of children with T2DM have a first or second grade relative with the disorder. The risk is increased if a parent develops T2DM before 30 years. Prenatal nutrition and the intrauterine environment affect risk; the low and high weight of birth and maternal gestational diabetes or T2DM are the greatest risk factors. Ethnic minorities are at greater risk, including African Americans, Hispanics and Native Americans. Finally, fat distribution plays a role; children who have central obesity with visceral or upper abdominal fat stores run a higher risk of RI and progression to diabetes. Second-generation antipsychotic patients (SGAPs) are another group with higher risk of weight gain and secondary diabetes. Among adults with schizophrenia and affective disorders taken by SGAP, the prevalence of diabetes is estimated at 1.5–2.0 times that of the general population. Pediatric literature is limited; however, a retrospective review of the chart estimated a 4-fold increase in diabetes among pediatric patients exposed by SGAP, compared to non-psychotropic drug users. An observational study of the metabolic effects of SGAP therapy on children found an average weight gain of 8.5 kg in 11 weeks. Clinical Practice for Hospital Weight Management Clinics for Children in Prediabetes and Diabetes Mellitus Type 2 All respondents, who represent 28 programs in 25 children's hospitals, indicated that they analyze patients of prediabetes and T2DM. Twenty-five clinics reported the criteria used for detection. Most (n=18 of 25; 72%) used the BMI as a criterion; however, cutting points vary between programs (four screen for BMI ≥95th percentile, three for ≥85th percentile, one for ±40 kg/m2, and one for ≥99th percentile or ≥95th percentile with comorbidities). Seven sites analyze all the patients mentioned. Additional factors used for target detection include nigrican acantosis (n=4), family history of T2DM (n=2), age (n=3) and clinical signs of diabetes (n=1). Focus on a Fitter Future Consensus Statement on Clinical Detection Children with cardiometabolic comorbidity and obese children should be regularly analyzed by prediabetes and T2DM after 10 years or after puberty (Evidence D). Early identification of the prediabetic or diabetic state can prevent disease progression or facilitate disease management. An additional study of the predictive value of abnormal blood glucose measures is needed for the development of T2DM in children. Laboratory Analysis and Diagnostic Tests ADA recommended tests for the detection and diagnosis of prediabetes and diabetes include fasting of plasma glucose (FPG), A1c, and oral glucose tolerance test (OGTT).The selection of tests for individual patients may vary according to clinical findings, risk factors and available resources. Relative advantages of fasting glucose and A1c as screening tests are listed in , and diagnostic cuts are listed in ., An analysis of the laboratory data of 1156 overweight and obesity teenagers of the National Health and Nutrition Survey 1999–2006 found that a 6.5 percent A1c cut was sensitive to 75% to identify diabetes, compared to a single FPG, although a very limited number of diagnosesses = The same study found that, for adolescents compared to adults, A1c was a significantly worse predictor of prediabetes defined by FPG (area under the operating curve of the receiver, 0.61 vs. 0.74; pTable 2.Comparison of Tests To Screen for Prediabetes Plasma glucose fastHemoglobin A1c• Higher sensitivity compared to A1c in adult populations (in adults up to one third more diagnosed)• It is not affected by the conditions associated with the high rotation of red blood cells (e.g. anemia, blood transfusion, pregnancy)• Less expensive and more convenient compared to OGTT• Low reproducibility• Fasting is not necessary.• Low intraindividual variability• Less daily variability with disease or stress• Reflects glucemic levels over the last 3 months• Good predictor of complications related to diabetes in adultsOGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; A1c, glucose hemoglobin. Table 3.Summary Criteria for Diagnosis Prediabetes and Diabetes, PrediabetesDiabetesd Plasmatic Glucosa decomposition100–125 mg/dL≥126 mg/dL2 hours of plasma glucose (OGTT)b140–199 mg/dL≥200 mg/dLRandom glucosec of plasma Not applicable OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; A1c, glucose hemoglobin. Insulin Resistance Index Accurate RI tests are intensive, invasive and face-to-work techniques (i.e. hyperinsulinemic-euglycemic and hyperglycemic techniques). Therefore, several indexes have been developed and studied, such as the evaluation of the homeostatic model of insulin resistance (HOMA-IR), the quantitative insulin sensitivity index, the continuous infusion of glucose with the evaluation of the model, and the Matsuda index. The most used and studied is HOMA-IR. There are no known international standards for abnormal levels currently for these indices in children, the trial itself is not standardized, and studies have shown that insulin indices do not substantially change the predictive value of diabetes beyond other more routine measures.The results of these studies highlight the concern that insulin levels can initially be a deficient predictor of diabetes risk because, while the RIs may go with insulin more Clinical Practice Results for Tests Used to Detect Prediabetes The 28 respondents reported on the detection of prediabetes, using a variety of test combinations. The most used tests were A1c (n=23) and FPG (n=22), with OGTT used less often (n=10). Three clinics used only A1c, five used fasting glucose alone, 14 used fasting glucose plus A1c, and six used the three tests for initial detection. Most respondents repeated normal laboratory tests in 12 months (n=9) or between 6 and 12 months (n=9). Some respondents repeated normal labs before, at 3-6 months (n=5) and later at 12–24 months (n=2). For abnormal laboratory tests, most repeated tests at 3-6 (n=9) or 6–12 months (n=8). A few (n=3) repeated screening tests according to needs. Results of Clinical Practice for Insulin Resistance Detection All respondents reported IR detection by evaluating for nigrican acantosis in physical examination. Twenty-five (88%) respondents were projected to IR using fasting insulin or a fasting relationship of glucose to insulin. A marked variability was observed in the criteria used to identify children to be analyzed: Thirteen clinics (52%) detected all children who were referred to for weight management. Of the 12 remaining clinics, four BMI percentile criteria used only (two Conf95th and two mento99th), six used the presence of nigrican acantosis and a BMI cut (one не85thil with risk factors and five percentile percentile), and two used a cut based on the beginning of puberty and BMI √85th percentile. Additional detection factors used included the family history of T2DM (n=3) and ethnicity (n=1). Three clinics that opt not to analyze insulin levels reported the following reasons: Data did not change management, the desire to retain financial resources, and the advice of the endocrinologists of the institution who recommended the detection of abnormal blood glucose measures only. Focus on a Fitter Future Consensus Statement on Clinical Detection through FPG, A1c and OGTT Laboratory Tests can be used to detect prediabetes in children who present tertiary weight management programs at the previous age of 10 years or beginning of puberty (Evidence B; see for details). The authors recognize the option for clinicians to select one or more available tests. Examinations can be considered in younger children with severe obesity or prescribed children. Authors do not support laboratory detection to fast insulin in obese patients because current evidence does not indicate results-based treatment changes, and insulin levels can be low as patients lose secret insulin capacity. Therefore, low levels of insulin can represent a deterioration of the beta-cellular state, rather than improving the IR (Evidence D). The predictive value of blood glucose and RI laboratory markers needs to be further studied with the time for T2DM progression, especially in severely obese children and other groups expected to be at greater risk. Prevention of type 2 diabetes Halting the progression towards T2DM, both from normal glucose regulation to prediabetes and from prediabetes to diabetes, is one of the key goals of obesity management. Several studies have shown that the lifestyle change that consists of physical activity, lower daily energy consumption and modest weight reduction can reduce the incidence of T2DM in adults with high risk of diabetes., T2DM progression usually occurs in individuals with overweight or obesity and sedentary. Resistance to the action of insulin in the liver and skeletal muscle can lead to hyperinsulinemia, often marked by the presence of nigricans of acantosis, especially in darker pigmented individuals. Pancreatic beta cells may eventually fatigue as RI gets worse, and insulin secretion waking leads to moderate glucose excursions in prediabetes. The insufficiency of more advanced beta cells, in the presence of persistent RII, results in T2DM overt as glucose toxicity further hinders insulin secretion and leads to blood glucose to rise uncontrollably. The intensification of early interventions in the course of disease, with the objectives of normalization and preservation of glucose of the pancreatic beta-cellular function, seems to offer the best opportunity to prevent the development of diabetes or to slow progress towards diabetes. While new cases of T2DM occurred in DPP intervention weapons over time, the incidence of T2DM remained below that of the control group. Therefore, the ADA Professional Practice Committee recommends that prediabetes adults be referred to a program that points to weight loss of 7% and increased moderate physical activity to ±150 minutes per week based on DPP data. Adolescent studies have also shown an increase in insulin sensitivity with weight loss induced by diet and exercise, and the resolution of prediabetes in multicomponent lifestyle programs. The role of the medication in the prevention of IR diabetes precedes the development of T2DM, which occurs when the pancreatic beta cells do not compensate for IR. Several large RCTs of pharmacological interventions have been carried out to decrease the incidence of T2DM of new appearance in adults with mixed results.Methformin, a biguanide, decreases the production of hepatic glucose and also increases insulin sensitivity in peripheral tissues. In the DPP trial, metformin, at a dose of 850 mg twice a day, showed a reduction of 31% in risk, compared to placebo, more than 2.8 years (compared to a reduction of 58% in the lifestyle group)., A meta-analysis of five randomized clinical trials of adults in metformin found a 40% decrease in progression to type 2 diabetes among those at risk. In obese teens, a meta-analysis that includes three randomized short-term metformin trials with IR found a reduction in BMI and the insulin of fasting with treatment. Three other small randomized trials in North-Moglycemic obese children with high fasting insulin showed a reduction in glucose and fasting insulin. However, none of these studies lasted more than 6 months. The findings of clinical practices for the use of metformin in prediabetes Among child hospital obesity programs, 14 out of 28 respondents (50%) indicated that they use metformin to treat prediabetes, and prescribed doses ranged from 500 to 2000 mg per day. Seven of these 14 clinics that treat prediabetes with metformin reported systematic follow-up of patients' results, including BMI and laboratory values. Eight respondents reported using laboratory triggers for endocrinology: high fasting glucose ratio100 mg/dL (n=4), abnormal GTT (n=3) and A1c ±5.7% (n=1). The reasons for stopping metformin included the improvement of blood glucose (n=5), the decrease in BMI of 2 kg/m2 (n=1), and the improvement of insulin (n=1). Three respondents indicated that an endocrinologist was routinely consulted regarding the decision to stop the metformin. Results of clinical practices for use of metformin in insulin resistance In addition to the use of metformin for prediabetes, 11 programs reported the prescription of metformin for high fasting insulin or HOMA-IR in the absence of abnormal blood sugar or polycystic ovarian syndrome. Focus on a Fitter Future consensus statement on prevention of type 2 diabetes mellitus using pharmaceutical products The Committee does not take a position on the use of pharmacological agents to prevent T2DM in children with high prediabetes or insulin, given limited studies in children and evidence that many children with prediabetes can return to normoglycemia without pharmacological treatment (Evidence C). The authors call for a long-term study of the safety and effectiveness of the treatment of prediabetes drugs to prevent T2DM in children, recognizing that the scale of the study should be large and the long duration, even when populations with the greatest risk of T2DM are targeted. Role of nutrition in diabetes prevention Support for healthy nutrition is essential for managing and preventing diabetes. Medical nutrition therapy with a registered dietitian provides specialized support to treat young people with prediabetes and T2DM. It should be noted that studies of dietary interventions discussed below have used registered dieters to design and deliver nutrition interventions. Weight loss from 5 to 7% is the standard recommendation for the prevention of adult diabetes based on DPP, which used a low-fat diet to lower calorie intake. Research studies are needed to report similar recommendations to young people, especially during critical periods of increasing international human rights standards, such as puberty. Studies suggest that lifestyle intervention in children also leads to metabolic improvement. Although there is no prescribed diet for the prevention of diabetes in young people, research on low-glycemic diets between adults and young people shows an improvement in insulin secretion and body composition without evidence of damage. A low Glycemic Index (GGI) diet usually refers to a balanced diet with carbohydrate content mainly from low-to-middle glycemic load foods (those that produce less rapidal increase in blood glucose and have lower carbohydrate content). The most common high-level foods include processed cereals (white bread and white rice) and added sugars of all kinds. In two studies that compare low and high GI diets in 38 young people with obesity and T2DM or prediabetes, the low GI diet had significantly higher reductions in RI. Additional research found a low GI diet decreased the fatty tissue more than low calories and low fat diets, and increased high-density lipoprotein cholesterol and satiety. A RCT comparing low-loading hypocalric diets versus high glycemic for 6 months found further reductions in the waist circumference, BMI z-score and HOMA-IR with the low GI diet. In severely obese children, few studies examined the safety and effectiveness of fast-weight diets. A study of 46 adolescents randomized to a low-calorie diet, low-fat or a very low-carbohydrate diet (20 g/day) showed safety and efficacy of the very low-carbohydrate diet. Another study that compares 58 randomized children with a very low carbohydrate ketogenic diet or a hypocalortic diet for 6 months found greater improvements with the weight cetogenic diet, fat mass, waist circumference, fast insulin and HOMA-IR. More comprehensive and long-term studies of very low carbohydrate diets are needed for severely obese prediabetes. Function of diabetes prevention Exercise, combined with healthy dietary changes through a behavioral approach, is a key therapeutic recommendation for reducing obesity and preventing T2DM. In adult studies, exercise increases insulin sensitivity within a week of intervention, which lasts for 3-4 days after exercise. In obese children, exercise alone has been shown to improve RI even without changes in body weight or body composition. Several exercise interventions have been tested, including 1 hour circuit training sessions three times a week, sports activities for 20–45 minutes three times a week and progressive resistance training. Individual differences in physiological changes with exercise depend on base fitness, genetic effects and lifestyle. Focus on a Fitter Future consensus statements on T2DM prevention using diet and physical activity The Committee supports dietary intervention to manage weight, specifically a low GI diet applied by registered dietitians, to influence metabolic risk factors for T2DM in prediabetic children (Level of evidence B). A more severe carbohydrate restriction may be considered for obese children with prediabetes under medical supervision. Further study is needed on the long-term effects of the diet on T2DM prevention in severely obese children and adolescents. For physical activity, although there are no pediatric recommendations for exercise specifically to prevent diabetes, the Committee strongly supports an increase in the level of moderate to vigorous physical activity for children with prediabetes (Evidence B). The AAP recommends 60 minutes of moderate to daily dynamic activity for all young people. Role of behavioral health professionals in diabetes prevention Standard practice for treating childhood obesity in multidisciplinary referral environments includes behavioral health services provided by a pediatric psychologist at the medical level, if possible. There are emerging literature that underlines the benefits of including a behavioral health specialist in T2DM treatment., Early participation of behavioral health professionals for those with prediabetes can help prevent disease progression. As in the treatment of obesity, behavioral treatment for the family unit of young people with prediabetes or T2DM can be especially important, given high T2DM rates and problem behaviors among family members. In addition to facilitating the change in family-based lifestyle behaviour, psychologists can address asrbid psychopathology that contributes to disease progression or makes treatment difficult. Emotional and behavioral difficulties represent barriers to adherence to pediatric medical regimes in general. Nearly 1 in 5 young people with newly diagnosed T2DM can have pre-existing psychiatric diagnoses. Researchers have found that the progression of IR during childhood and adolescence is predecided by depressive symptomatology at the base, independent of the BMI. Psychologists can also be critical to addressing other barriers of accession, such as family conflicts and poor time management. Psychologists can help a multidisciplinary team in providing culturally effective pediatric care. Children and adolescents at low socio-economic levels, minority ethnic groups and single-parent families tend to have more problems with adherence to complex chronic disease regimes. In general, racial and ethnic minorities use mental health services at lower rates than non-Latin targets. Therefore, pediatric psychologists working with children and adolescents with prediabetes must be sensitive to cultural problems and adapt their interventions to each family. Focus on a Fitter Future Consensus Statement on the Role of Conductive Health Professionals in T2DM Prevention The Committee supports including paediatric psychologists or other trained behavioral health specialists, in care teams to manage prejudices using behavioral treatment approaches (Evidence C). Referral to Endocrinology/Diabetes ADA's recommendations indicate that children who meet the criteria for T2DM should be referred to endocrinology specialists to confirm diagnosis and discuss drug decisions and how to manage comorbidities. An endocrinologist should be consulted to distinguish between type 1 and 2 diabetes. The AAP recommends that weight management specialists co-manage T2DM with a pediatric endocrinologist. A primary care professional (paediatric, family or internist) who has experience in managing diabetes can serve as a consultant in the absence of a pediatric endocrinologist available. Clinical findings for co-management with an endocrinologist While some pediatric obesity clinics are run by an endocrinologist, others have more limited access to endocrinologists. Nearly all child-hospital obesity clinics in our survey (n=23 of 25; 92%) do not include endocrinologists in the weight management team; all these patients refer to endocrinology T2DM, mainly for drug management. Most respondents (n=16 of 22; 72%) indicated that they do not refer to patients with prediabetes to endocrinologists. Focus on a Fitter Future consensus statement on T2DM co-management with an endocrinologist Consequent to AAP recommendations, the Committee supports that the co-managed T2DM weight management specialists with a pediatric endocrinologist (Evidence D). Conclusion Given the highest prevalence of prediabetes and T2DM among children, it is necessary to guide the detection and management of prediabetes in order to ensure the best clinical results and reduce the costs of medical care. However, data to guide T2DM prevention in children are limited. This article summarizes the current literature on the detection and diagnosis of prediabetes and the prevention of T2DM among overweight youth. The variability in RI and prediabetes assessment and treatment practices can be attributed to the lack of high quality testing and limited availability of pediatric endocrinological knowledge. Based on the best available evidence, our experience in the treatment of obese children and in the review of potential damages and benefits, the authors provide support statements that reflect the consensus of the FFF Medical Management Committee, taking into account the level of evidence, the uniformity of current practice, the potential costs and benefits of the practices reviewed (). Table 4.Summary of support for practices in the treatment of childhood obesity for prediabetesPractice Evidence qualityA= well-designed randomized trials or B=trials with minor limitations diagnostic studies; heavily consistent observational studies C= observational studies or controlled trials with significant limitations D=experienced opinion, case reports, principled argument Balance of benefits for the preponderance of damages in relation to damages and benefits superior to the greatest benefits. Current practice in obesity treatment programs-Varied-Consistents-Non reported in this surveySupport for practice-Apoyo-Apoyo-Option to consider-No Position-No SupportComments on need for study Children with overweight with cardiometabolic pubrability and obese children should be analyzed by prediabetes or type 2 diabetes after 10 years or after 10 years. Treatment of obesity in children with prediabetes or insulin resistance leads to an improvement in prediabetes and/or insulin resistance, but no study has examined the prevention of T2DM progression in children. In accordance with the recommendations of the Committee of Experts. Greater Damage Benefits: Financial cost, test-related anxiety, risk of false positives Benefits: The benefit of lifestyle intervention for prediabetes in adults is documented; the benefit of detection and preventive treatment is not so well known for adolescents. Programmes can allocate limited weight management resources to those at greater risk. Consistent: All centers reported evidence. Varied: The centers vary with respect to the selection criteria by BMI status, age and other risk factors. SupportLarge, prospective tests are needed to determine the effect of weight management treatment for the prevention of progression of prediabetes to T2DM. An additional study is required to test the effectiveness of treatment for T2DM that is first detected by selective detection. Glucose in plasma, hemoglobin A1c (A1c) and OGTT can be used to detect prediabetes in children with tertiary weight management programs. BStudies studies support the use of these tests to make a diagnosis, but are limited by small sample sizes or extrapolation of adult studies. Test cuts are not so validated in children, especially for prediabetes. Greater Damage Benefits Damage: Financial cost and risk of false positives/negative benefits: Sensitivity, specificity, cost and comfort vary according to test (see ). Consistent: Most centers use both A1c glucose and fasting. Varied: Varied and old BMI cuts are used to start detection; tracking test protocols also vary in frequency and test choice. SupportRecognizing the clinician's option to select from one or more of the available tests More research is needed to define the test protocol with maximum sensitivity and specificity to the lowest relative cost. Insulin resistance tests by fasting insulin and/or HOMA-IRDEvidence lack the benefits of using insulin detection. Higher Benefits Damage: Financial cost, lack of standardization in laboratory measures Benefits: Unknown; there is no evidence to support changes in insulin-based management; insulin level does not predict progression to T2DM; low insulin may reflect insulin resistance or beta cell failure. Varied: Most tested insulin programs, but based on variable BMI and comorbidity criteria. Some centers have collected this as part of a research study and some use this as criteria for dealing with metformin. No Support More in-depth study is needed to determine the value of insulin laboratory measurement for the prognosis or objective of interventions. Costs currently exceed the lack of known benefits. The use of metformin to prevent the progression of prediabetes to T2DMCMetformin is less effective than the intensive management of adult lifestyle. The consistent observational evidence shows reversal of normoglyemia in a high proportion of prediabetic youth without medication. Harmful drugs: The cost of medicine given the prevalence of prediabetes is relatively high; short- and long-term adverse effects. Benefits: Unknown because the prevalence of T2DM is low and the effect of metformin on T2DM prevention in prediabetic children is unknown. Varied: More than one third of the programmes (39%) prescribes metformin. No Position There is a need to study more thoroughly the effects of the medication on T2DM prevention, including setting endpoints to finish the medication. A large number of high-risk T2DM young people would have to be enrolled in a final study. Low-glycemic index diet to treat prediabetes in obese youth High-quality and low-quality studies constantly show metabolic improvements with low-glycemic loading diets. Major Damage Benefits Damage: Cost of dietary instruction, financial costs to families associated with dietary change Benefits: Metabolic improvement, potential weight loss Not reported Support More in-depth study is needed to quantify the effects of low-glycemia rates and other diets, including very low carbohydrate diets, on T2DM prevention. Increased moderate to vigorous activity to treat prejudices in obese youth Physical activity is constantly correlated with better glucose regulation in obese children, independent of weight loss. Clear preponderance of Damage Benefits: Risk of injury, time required for exercise Benefits: Metabolic improvement, potential weight loss, other health benefits of exercise Not reported Strong support Further study is needed to quantify the effects of exercise dosage and type in preventing T2DM on children. Pediatric psychologists or other behavioral health specialists should be included in teams dealing with children with prediabetes or diabetes. High rates of psychological comorbidity exist among children with prediabetes/diabetes. Behavioral change is the pillar of effective weight management, with evidence that supports its effectiveness. Clear Preponderance of Damage Benefits: CostoBenefits: You can improve weight results, address psychopathology Not reported Strong supportThe treatment of multidisciplinary equipment, including behavior specialists, is the standard of care for the treatment of stage 3 and 4. Weight management specialists co-manage T2DM with a pediatric endocrinologist D This practice is recommended by the clinical practice guideline AAP: "Management of Newly Diabets Mellitus (T2DM) in Children and Adolescents."Benefits outweigh harmrins CostoBenefits: Expertise in medication management and surveillance for medications that are used infrequently pediatrics Pediatric endocrinologists may not be available in all areas. An additional study should evaluate the best way to facilitate co-management in areas where sub-specialists are missing (e.g. telemedicine). HOMA-IR, evaluation of homeostatic models for insulin resistance; T2DM, type 2 diabetes mellitus; A1c, glucose hemoglobin; OGTT, oral glucose tolerance test; AAP, American Academy of Pediatrics. More research is needed to guide which therapies might prevent the progression of prediabetes to T2DM and which children should be targeted. In order to answer important clinical and public health questions, large-scale studies of multiple intervention centers are needed to reduce the risk of T2DM. A multicenter research network of child obesity treatment programs, collaborating with multidisciplinary teams, including pediatric endocrinologists, could provide the necessary platform to respond to many of these questions. Acknowledgements Between 2008 and 2013, the CHA (formerly known as NACHRI, the National Association of Children ' s Hospitals and Related Institutions) convened FFF to articulate the role of children ' s hospitals in combating pediatric obesity, while establishing consensus on performance measurement and quality improvement. The FFF examined the state of care of obese children and adolescents and continues to communicate the best ways to ensure their physical well-being and emotional security. FFF was guided by multidisciplinary teams representing more than a dozen pediatric health professions—physicists of various specialties, dietists, exercise specialists, nurses, physical therapists, obesity programme directors, psychologists and social workers—involved with child obesity. This article represents the work of the Medical Treatment Committee in consensus with the entire FFF group. FFF was partly funded by the Mattel Children's Foundation. Dr. Haemer was supported by the Research Fellows Award at the Colorado Children's Hospital Research Institute. Dr. Rhodes was supported by the New Balance Foundation Obesity Prevention Center Boston Children's Hospital. Author Disclo StatementCHA (the Association) was the sponsor of the project. The sponsor facilitated the collection of data and the meetings of host study groups, but did not participate in the analysis of data or in the decision to present the manuscript for publication. The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Association. Dr. Rhodes reports that he received research funding from Merck, and his spouse has shares in Bristol-Myers Squibb. The remaining authors have no information. ReferencesFormats: Share , 8600 Rockville Pike, Bethesda MD, 20894 USA

Prediabetes: How to identify children at risk

Prediabetes: How to identify children at risk

Prediabetes: How to identify children at risk

Prediabetes: Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis and Treatment - Causes, Symptoms, Diagnosis, and Treatment

ISDH: Prediabetes

Prediabetes in Children and Adolescents: What Does It Mean? – Wisdom's World

Diabetes Prevention is Possible

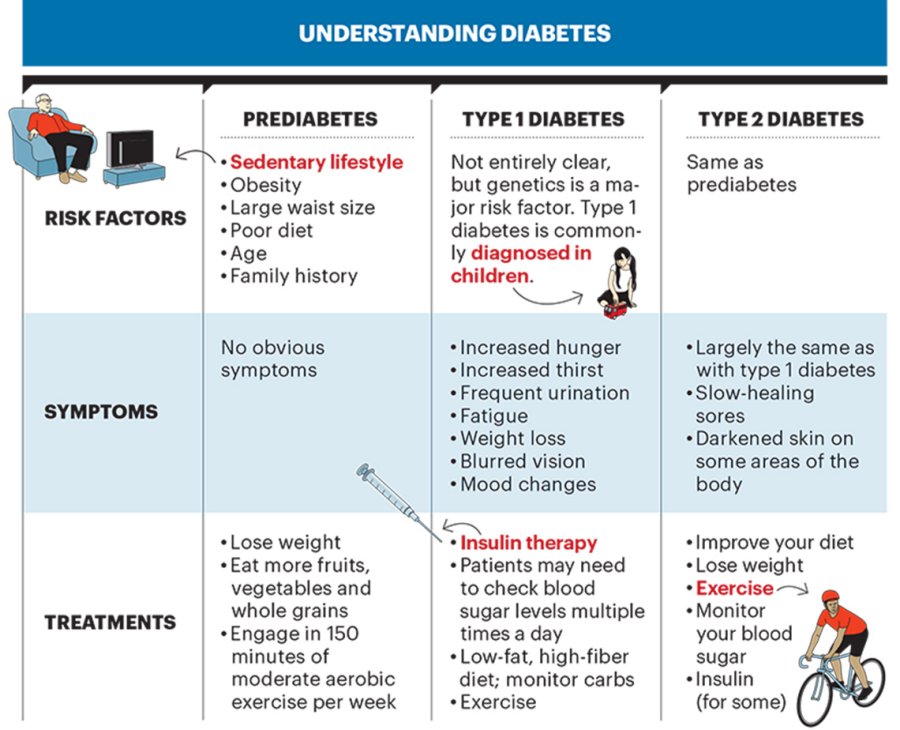

Diabetes Infographic | Types, Symptoms & Causes

Prevalence of prediabetes and diabetes in children and adolescents with biopsy-proven non-alcoholic fatty liver disease - Journal of Hepatology

Type 2 diabetes

Children and Diabetes - Diabetes in Childhood

Diabetes Infographics | Social Media | Press & Social Media| Diabetes | CDC

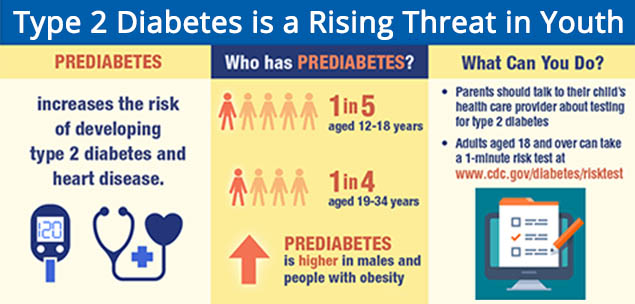

Prediabetes on the Rise in Children: How We Can Stop It

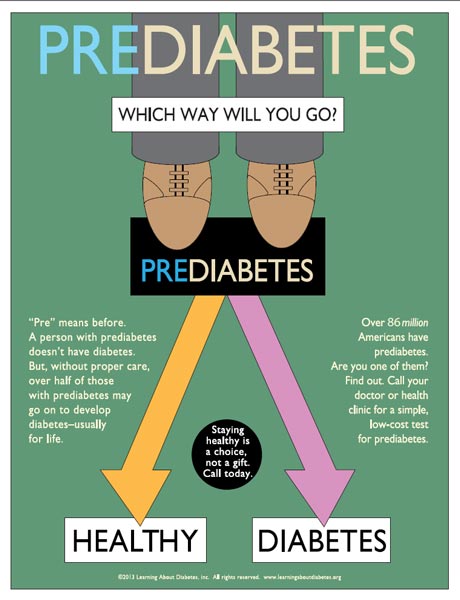

Diabetes Information PDF Forms for Consumers : Learning About Diabetes, Inc

What Are the Symptoms of Type 1 Diabetes? - How to tell if you or your child has type 1 diabetes

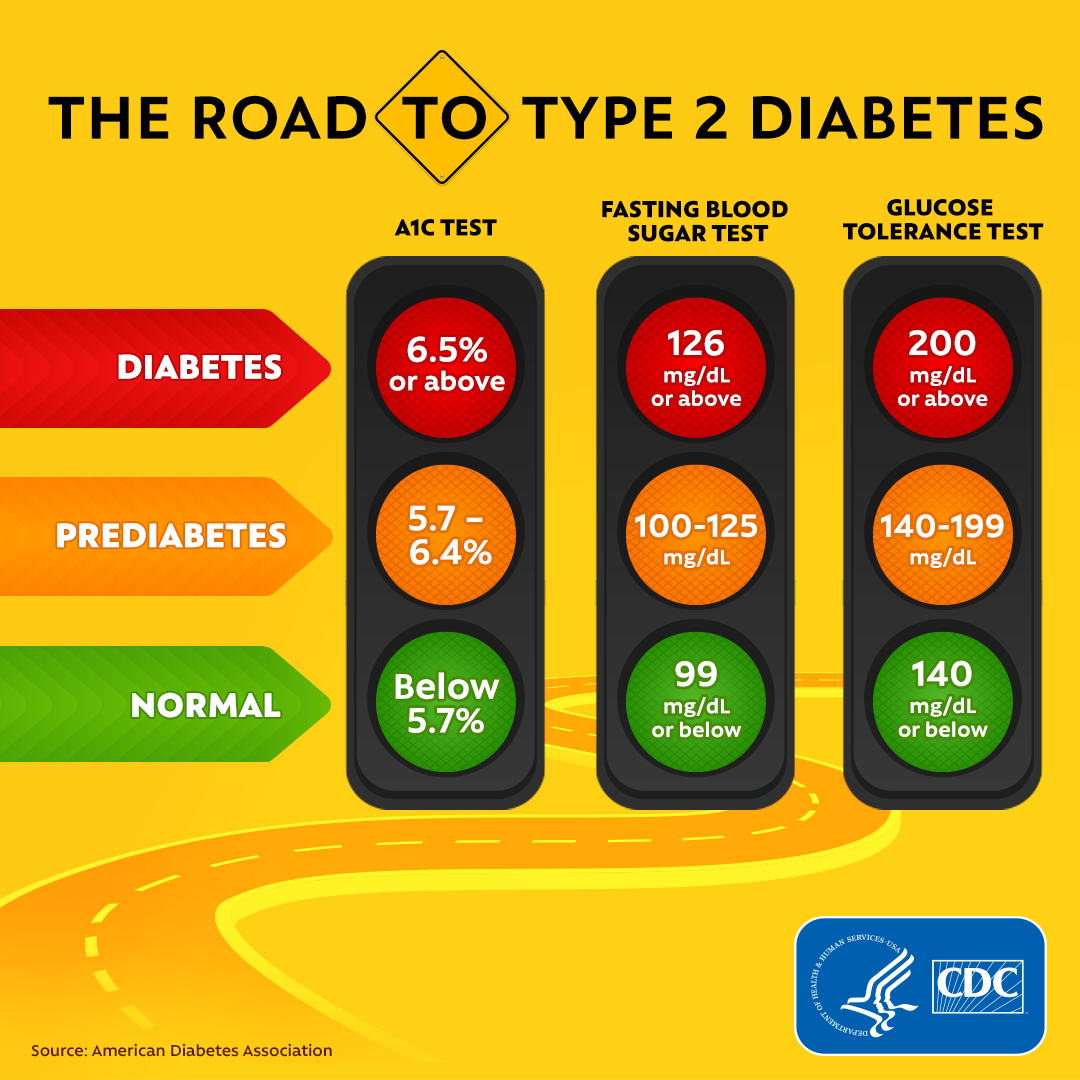

Diabetes Tests | CDC

Prediabetes in Children | Lark Health

Type 2 diabetes in children: Symptoms, causes, and treatment

Child Weight Loss MD: Early sign of pre-diabetes

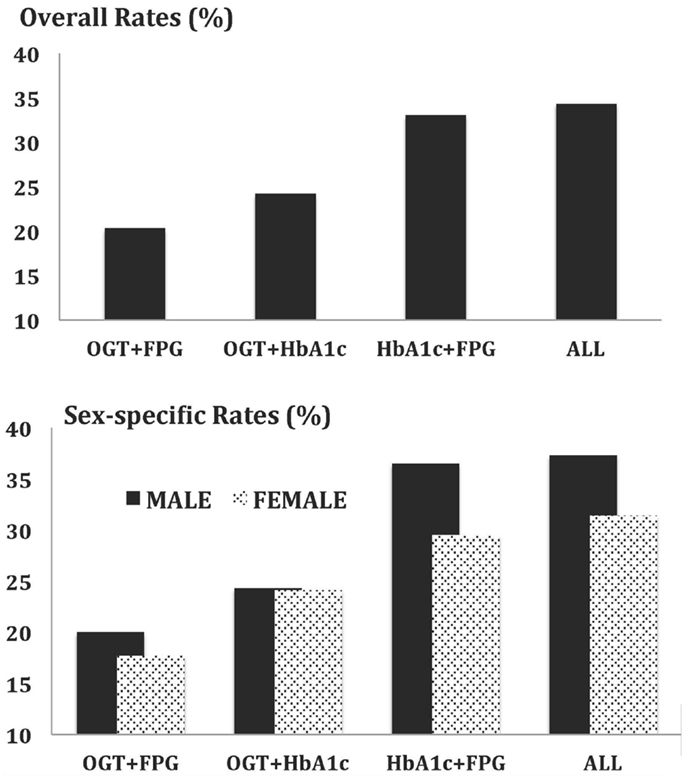

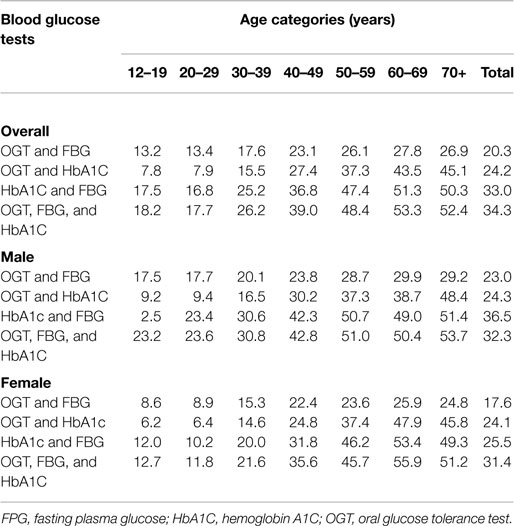

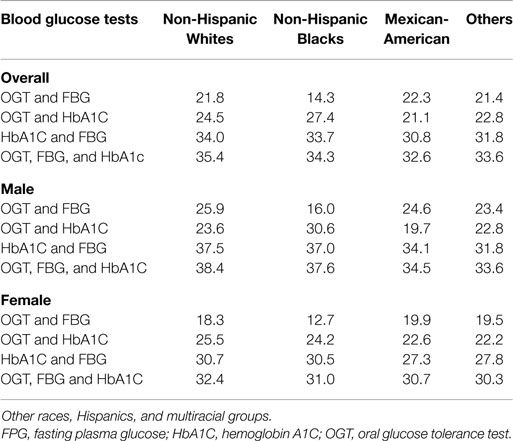

Frontiers | Improving Detection of Prediabetes in Children and Adults: Using Combinations of Blood Glucose Tests | Public Health

Type 2 diabetes: Symptoms, early signs, and complications

Pin on Diabetic Diet Lifestyle

Prediabetes in Children: Risks, Causes, and Prevention - GoodRx

War on Diabetes | SingHealth Regional Health System

Prevalence of Prediabetes in School-Going Children

Frontiers | Improving Detection of Prediabetes in Children and Adults: Using Combinations of Blood Glucose Tests | Public Health

25% of Kids Have Prediabetes, and Most Don't Know It. — Lakanto

Summary of Support for Practices in Childhood Obesity Treatment for... | Download Table

Type 2 Diabetes in Children: Symptoms, Risk Factors, Treatment, & More

Frontiers | Improving Detection of Prediabetes in Children and Adults: Using Combinations of Blood Glucose Tests | Public Health

Prediabetes Signs, Symptoms and Treatment Guide | Lark Health

Type 1 Diabetes Symptoms, Causes, Diagnosis and Treatments - Causes, symptoms, diagnosis, treatments, and support

Can You Have Prediabetes and Not Know It? | Get Healthy Stay Healthy

Prevalence of prediabetes in children and its association with risk factors | Semantic Scholar

Prediabetes in children

Tips for turning around a pre-diabetes diagnosis in your child or teen - YouTube

Diabetes Arkansas Department of Health

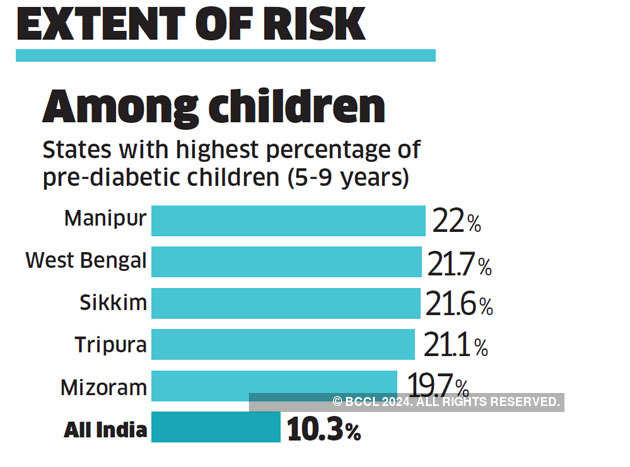

Why India should seriously pay attention to its children's pre-diabetes - The Economic Times

How to prevent pre-diabetes | Childhood pre-diabetes

Recommended Tests for Identifying Prediabetes | NIDDK

Posting Komentar untuk "pre diabetes in children"